At Mount Vernon, learning begins with questions. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Middle School Maker, Design, and Engineering (MDE) program, an intentionally designed, inquiry-driven experience that provides every student with access to meaningful, hands-on learning.

“I think the message about Middle School MDE is around access,” says Chris Andres, Middle School MDE educator in his fourteenth year at Mount Vernon. “Everybody has access to this. All students. Whether you think you’re ‘this type of learner’ or ‘that type of learner,’ this space is for you.”

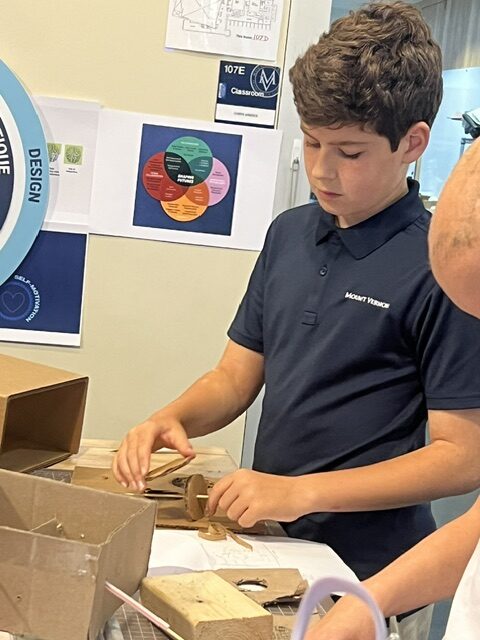

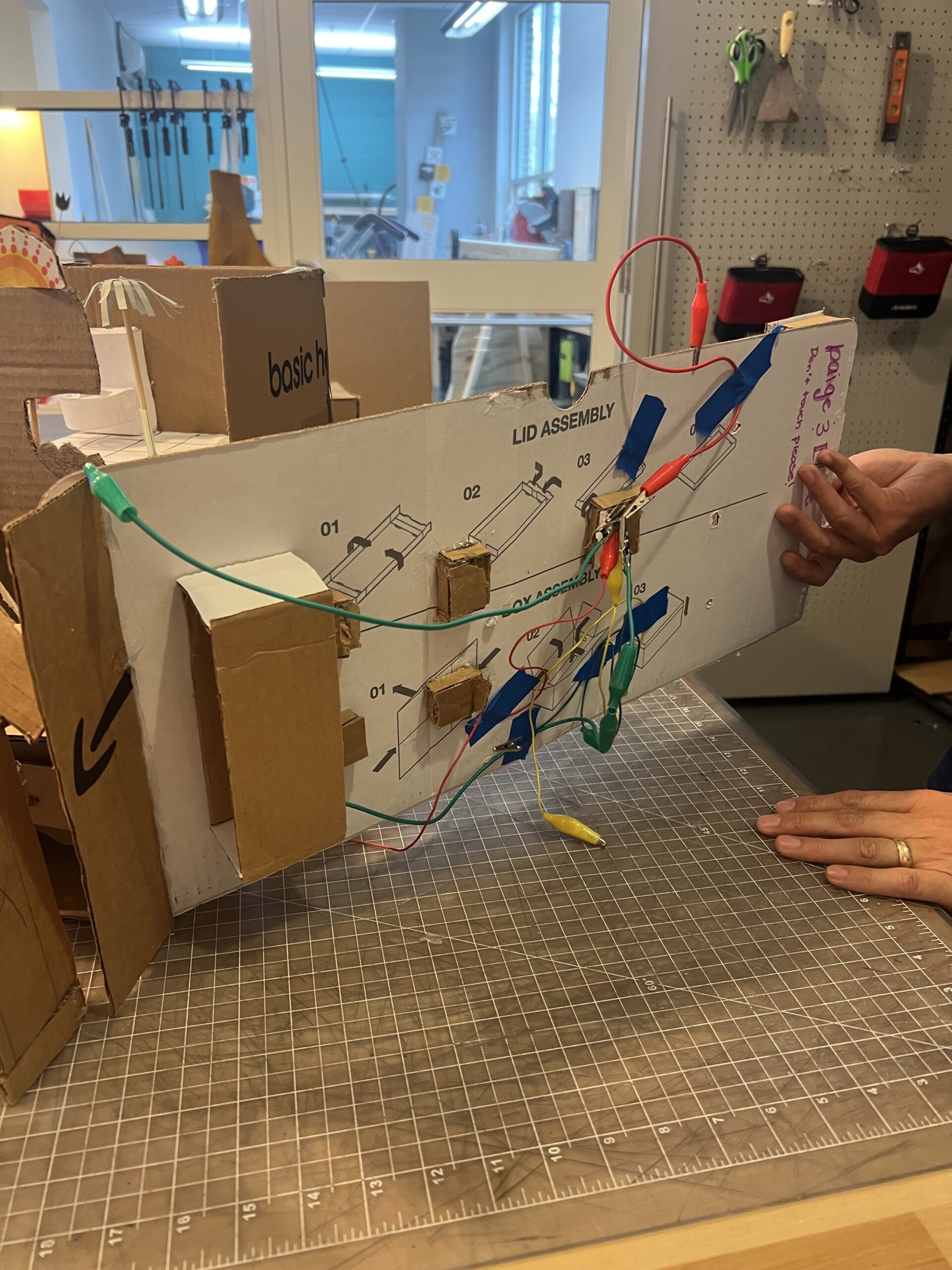

That commitment to access was on full display at the Christmas Art Showcase, where cardboard prototypes, circuitry, mechanics, and works-in-progress filled the gallery. At first glance, the projects appeared varied, with some polished and others intentionally rough. But each one told a deeper story of learning.

“Not everything you see is the finished product,” Andres explains. “Each of those pieces is a demonstration of learning and what the students understood.”

In MDE, students aren’t just building, they’re learning how to think. Instead of rushing to a final product, they focus on foundational skills: joinery instead of excess duct tape, purpose-driven design instead of guesswork, and iteration instead of perfection.

Joinery is the craft of joining pieces of wood (or similar materials) to create larger structures like furniture, cabinets, doors, and stairways, using methods that range from simple fasteners to intricate, traditional wood-only connections like dovetails, mortise-and-tenons, and lap joints, emphasizing both structural strength and aesthetic appeal.

“When students understand the parts, the purpose, and the complexity,” Andres says, “they know where to fix something because it’s theirs.”

That ownership is at the heart of Mount Vernon’s inquiry-based pedagogy. Students are encouraged to ask really good questions and then follow those questions wherever they lead. One project asked students to create an automata toy to help tell a story to non-readers. Talia Requena, remarked being able to make four prototypes before landing on the last iteration. The mechanics were important, but they weren’t the point.

Automata toys use hand-powered mechanisms to create movement. An axle rotates, causing the cam to turn as it is attached to the handle.

“The build is just the vehicle,” Andres explains. “What really matters is the idea the student is trying to communicate.”

In another case, a student applied those same maker skills to a Humanities project, designing a prototype for a self-cleaning bathroom to support unhoused populations. The result wasn’t just a model, it was a tangible expression of empathy, systems thinking, and problem-solving. Isabel Varano explains, “using the automata build was a more effect way to show how my design works rather than just writing about it.”

“It’s a paper and pencil for the idea,” Andres explains. “I can tell you about it all day long, but when I demonstrate it, you understand it differently.”

Throughout the MDE journey, learning is intentionally designed to evolve. In the Lower School, projects are more scaffolded, providing students with the time, structure, and guidance to develop foundational skills and explore tools safely.

By the time students reach Middle School, that foundation creates space for greater independence and complexity. The work becomes less scripted, more iterative, and deeply personal.

“In Middle School, it gets messy because it’s their idea,” Andres says. “They’re not making my stuff. They’re making their own.”

That messiness is intentional. It creates space for curiosity, iteration, and deep understanding—skills that last far beyond the Maker Space.

“When students ask the questions,” Andres says, “they own the answers and the journey toward them.”

Ultimately, Middle School MDE is about empowering curious thinkers.

“These tools don’t live here,” Andres says. “They just happen to be housed in this space. The ideas live everywhere else.”

And that may be the most powerful design of all.